Bundelkhand Beyond Khajuraho : architectural heritage of Bundelkhand

Bundelkhand Beyond Khajuraho : architectural heritage of Bundelkhand

Chasing the stunning architectural legacy of the Chandellas up and down the ancient land of Jejahuti in the Bundelkhand region of central India.

The

guide was clearly having a good time. Pointing at a gorgeous sculpted panel on

the wall of the Lakshmana Temple, featuring a host of sensuous maidens in

languorous poses, he asked a gaggle of college kids from Bhopal, “Who can tell

me which girl here looks like Pamela Anderson?” He was greeted with silence and

some embarrassed sniggers. Then one girl timidly raised her hand. “That one?”

she said, pointing at a surasundari admiring herself in a mirror. “She is

correct!” announced the guide, looking triumphant. “These beautiful women were

like Kareena and Katrina of their times. Supermodels!” he added, with a

flourish.

The

guide was clearly having a good time. Pointing at a gorgeous sculpted panel on

the wall of the Lakshmana Temple, featuring a host of sensuous maidens in

languorous poses, he asked a gaggle of college kids from Bhopal, “Who can tell

me which girl here looks like Pamela Anderson?” He was greeted with silence and

some embarrassed sniggers. Then one girl timidly raised her hand. “That one?”

she said, pointing at a surasundari admiring herself in a mirror. “She is

correct!” announced the guide, looking triumphant. “These beautiful women were

like Kareena and Katrina of their times. Supermodels!” he added, with a

flourish.

Another guide claimed that ancient India had everything, including designer purses. The evidence was a pretty little niche sculpture which showed a woman handing over a piece of jewellery to her attendant who was carrying the said purse. “I was showing this to some Italian tourists the other day. They said it was a Givenchy!” I’d expected all this to be annoying, but faced with the unearthly brilliance of the Khajuraho temples, it was easier to be amused instead

Paroma and I had arrived that very day by the early morning train from Delhi and had driven away from Khajuraho towards the Ken River, some 15km away, there to be the guests of wildlife conservationists Dr Raghu Chundawat and Joanna Van Gruisen at their lavish forest resort, The Sarai at Toria. Joanna and I had been exchanging emails the past few days, trying to fix on an itinerary. I wasn’t in the neighbourhood for Panna Tiger Reserve, the usual destination for guests at the Sarai, and not even strictly for Khajuraho, but to explore the countryside for other rumoured Chandella-era ruins.

The Chandella kings of Khajuraho had been a powerful local clan of Gond tribal stock who had risen to prominence in the 9th century CE, like countless other royal families of that time, by inventing a convenient myth for themselves, claiming descent from the moon god. Elevated to the caste status of chandravamsiya kshatriyas, over the next century they rode the tide of military belligerence to become a major power in north-central India. Thereafter, they embarked on an ambitious building project across their kingdom, which resulted in Khajuraho’s sandstone wonders. The dynasty had imagined Khajuraho as their sacred centre, filling it up with temples, monasteries and lakes. But they didn’t stop there. What isn’t very well known is that these indefatigable builders had left behind many more signposts of their refined aesthetics in Bundelkhand, which was then known as Jejakabhukti, or more commonly, Jejahuti. Bisected by the Ken River, the Chandellas’ core territory consisted of Khajuraho and the capital Mahoba to the west; and the two imposing Vindhyan fortresses of Ajaigarh and Kalinjar to the east. All these sites still have excellent Chandella remains, and I wanted to see them.

It was possibly my tiredness, or perhaps the somnolence-inducing heat of the noonday sun, but after making my way through the chief temples of Khajuraho’s western group of monuments, my head was spinning like a top. Actually, I think it was the richness of the sculptures, and the concentration required to take it all in. The sun gleamed off the delicate sandstone arms of the innumerable deities. The ascending pyramid of subsidiary shikharas of the Kandariya Mahadev Temple seemed to rise into infinity, making me giddy. The leaping vyalas, mythical beasts that were half-dragon, half-horse, sought to escape the niches of the kapili walls (the fluted columns on the side of the temples); amorous couples gloried in their bodies, all supple lines and loving expressions. There was biting sectarian satire too, on the walls of the Lakshmana and Jagadamba temples—images of pious-looking monks depicted in flagrante delicto, as well as the sculptural equivalent—in the form of upside-down sex on the wall of the Kandariya—of the literary tradition of sandhyabhasa or the twilight language, replete with puns and metaphors, a multilevel text.

A carousel of sandstone elephants, horses and soldiers,

musicians, dancers and siddhas went round and round the temples, in a

never-ending perambulation around divinity. The grand old man of Indian

archaeology, Alexander Cunnigham, during his tours of Bundelkhand as director of the

newly-formed ASI in the latter half of the 19th century, had actually counted

the number of individual sculptures on Khajuraho’s 21 temples—Shaiva, Vaishnava

and Jaina. Kandariya alone yielded up 872 pieces, each between 2.5 to 3 feet

high.

Alexander Cunnigham, during his tours of Bundelkhand as director of the

newly-formed ASI in the latter half of the 19th century, had actually counted

the number of individual sculptures on Khajuraho’s 21 temples—Shaiva, Vaishnava

and Jaina. Kandariya alone yielded up 872 pieces, each between 2.5 to 3 feet

high.

Paroma and I retired to the Sarai to plan our sorties over some excellently brewed coffee. Joanna showed me to the library and very helpfully handed me a bunch of books on Khajuraho, Cunningham’s survey report and one on the forts of Bundelkhand. The latter was very useful, as I knew next to nothing about Ajaigarh and Kalinjar, our next destinations. A part of me felt like staying put and luxuriating in the sunshine pouring into the large and pretty woodand-mud living area of the Sarai, with breakfast and lunch in the garden, the silence broken only by the twittering of innumerable birds. The staff, locals all, are hospitable and pleasant without the obsequiousness of larger resorts.

While the comfort of our pastel-shaded cottage beckoned, the itch to travel was on me. The next day, carrying a lunch hamper packed by Raghu, we set off for the forts, with our guide, a local lad called Jaipal. Hopping on the NH-75, we crossed the Ken and headed east through the Vindhyan forest of the Panna Tiger Reserve. Taking the SH-49, we then drove north for about an hour, over the flat plains of Bundelkhand, broken occasionally by looming outcrops of the range. Just outside of Panna, we passed a rudimentary diamond mine, a reminder of how mineral-rich the area still is. In the olden days, these flat-topped looming hills often provided the best site for fortresses.

Ajaigarh’s thickly forested ridge shields a large village of the same name, as shockingly clean and tidy as the rest of Bundelkhand. Right at the end of the village, a set of steep stairways lead up to the ramparts of the fort through a teak forest. Tradition has it that the fort was founded by a mythical ruler called Ajaypala. However, Jayapura Durga, as it was known, was probably first settled by the Chandella king Kirtivarman in the early 11th century CE, to celebrate his victory over the Kalachuris. During the latter part of the Chandella reign, when the king Paramardideva lost his capital Mahoba to Prithviraj Chauhan in 1182 CE, it became the administrative capital of the kingdom.

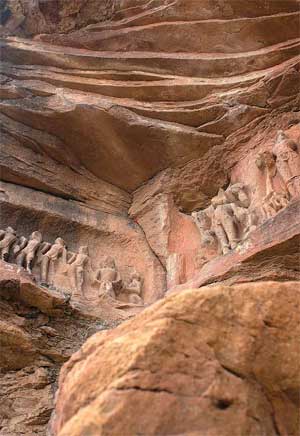

Ajaigarh is a gem. The moment you enter the first gate, you come across a finely sculpted statue of a dancing Ganesha, with a long inscription in medieval chitra-varna script, celebrating the setting up of the image. As I walked up the stairs, past two smaller gates, the rock face came alive with carvings. A group of meditating Jain monks here, a group of tirthankaras there and countless images of people worshipping shivlings, a carving of Mahishasuramardini and countless small yoginis. Past the Mughal-era gate called the Kalinjar Darwaza, the trail turned up into the hill, past two Chandellaera tanks called Ganga and Jamuna, and entered a thick teak forest. Giant granite blocks of once-lavish palaces and houses that once populated this fort lay strewn all around. One trail led past ruined architectural fragments to a large lake called Ajaypala talao. A small whitewashed shrine that’s a cross between a dargah and a Bundela-style temple housed a black stone idol of Vishnu, worshipped by local villagers as Ajaypala. Legend has it that a British officer once had the idol thrown into the tank to show his disdain for idolatry. He subsequently fell violently ill and didn’t recover till the idol was restored.

While I was wandering around the tank, a family from Ajaigarh walked up barefoot to pay their respects to the shrine. One of the men grinned at me and asked in broken English, “Which country you from? Like Ajaigarh?” When I smiled and replied in Hindi that I was from around here, he grinned back and said, “Damn, there goes my chance of practicing English!” and walked on.

Jaipal had been bringing up the rear and he’d led Paroma down a different trail to a group of ruined Chandella temples in the middle of the forest. I asked some goatherds about the way. They said they called it Rangmahal and gave me a rough route to follow. I soon hit upon the trail and followed it to a gate marked by the ASI. Beyond it, lay something right out of Indiana Jones, as Paroma later remarked. It was a group of three temples, of which two were built in the mature style of the Khajuraho temples. Partly destroyed, these were husks of what must have been structures at par with the Khajuraho group. Only their mandapas, garbhagriha and the kapili walls were standing, and their gorgeously sculpted interiors lay open to the wind and the rain. Surrounded by the forest, the temples presented an arresting sight. Joanna had told me that the place reminded her of how Khajuraho must have looked like when it was ‘discovered’ in 1832 by a British engineer called T.S. Burt. She was correct, and somehow, these eerie temples had a presence that the currently manicured lawns of the Khajuraho complex couldn’t really match. Sculptures of Bhairavas and yoginis were everywhere. The third temple was of a different style, and looked older.

A short walk from this group brought us to another ruined temple, next to a large tank called Parmal talao. Parmal was the nickname of the last major Chandella monarch who had retreated to Ajaigarh and Kalinjar following his defeat to the Chauhans. In 1203, he was to lose Kalinjar to the forces of Qutb-ud-din Aibak, and was assassinated by his minister for surrendering the fort. Before these reverses he was something of a playboy and a successful king. The tank was dug to quarry stones to build the temple. Later, it was converted into a waterbody with a rock-cut ghat for the exclusive use of the royal women of the palace.

A trail led away from the temples towards the southern ramparts of the fort, past a Mughal-era kiledar’s (master of the fort) post to the southern gate, called the Tarhaoni Darwaza, after a village of the same name on the plains below. A stunning set of carvings adorned the rock face here. A panel of eight large yoginis, sternly seated on corpses, meditating. One of the yoginis was depicted running, holding a flaying knife and a severed head. The tantric yogini kaula cult had flourished all through the Chandella domains around the turn of the first millennium CE. The clearest evidence of this was the rectangular Chausath Yogini Temple, Khajuraho’s earliest, that we’d seen the previous day. This seemed to be a veritable yogini pitha. Beloved of tantric Mantramarga and Kaulamarga Shaivas, as well as Vajrayana Buddhists (there’s evidence of the latter in Khajuraho), yogini and matrika shrines were usually found at the edges of citites and towns, and this was literally the edge of the fort, the ridge dropping down some 600 feet to the plains below. Apart from these, a large panel seemed to depict the five Pandava brothers and Draupadi. The area was also something of a fertility shrine, with images of a cow and a calf, a sow with her young, as well as a Shitala or Hariti with a child on her lap. On one side of the wall were a row of tiny, meditating monks. A long inscription just below the yoginis from about 1300 CE gives a list of Chandella kings beginning with Kirtivarman.

We still had another fort to cover, so we retraced our steps and drove off towards Kalinjar, just across the border in UP. We still had our lunch to eat. So we stopped the car beside the road, and had an impromptu picnic. Raghu makes a killer lemon pickle and we devoured parathas, sabzi and omelettes with it, along with plenty of water. Tramping about Ajaigarh had left us dehydrated.

Fortunately for us, you can drive all the way up to Kalinjar. Looming over a village of the same name, it’s one of the most renowned forts of India, once named Kanagora by Ptolemy. It has been a settlement for at least two millennia, as well as a sacred spot. The title of Kalinjaradhipati, or the ‘Lord of Kalinjar’ was a coveted one, one that was borne by the Kushanas, Kalachuris, Guptas and the Gurjara Pratiharas till the Chandellas acquired the fort and held it for over 200 years. Standing at a strategic point on the Indo-Gangetic plains, the sheer walls of the fort seemed to grow out of the hill itself, and it looked nigh on unassailable. As we drove towards it through the hinterland, the hill appeared first, blue on the horizon, looking impossibly huge. When we got closer, the ridge-top started bristling with battlements.

The Chandella king Vidyadhara, who commissioned the Kandariya Mahadava Temple, successfully defended the fort against Mahmud of Ghazni twice, in 1019 and 1023 CE. When Prithviraj Chauhan attacked the Chandellas he pillaged Mahoba, but had to retreat from Kalinjar. Qutub-ud-din Aibak’s army succeeded in 1202 only because the fort ran out of water. Aibak’s historian praised the victory by calling Kalinjar the strongest fort in the world, second only to Alexander’s. Much later, Humayun failed twice to take the fort from a Chandella chieftain, and Sher Shah died capturing it. The British had to bribe the chief who held the fort to be able to commandeer it.

Today, Kalinjar is a ticketed ASI monument, and is littered with the remains of 1,500 years of history—Gupta, Chandella, Delhi Sultanate, Lodhi, Mughal, Bundella and British. However, it is Kalinjar’s spiritual history that’s still a vital, living presence. A site of Shiva worship from the times of the Puranas, the cave temple of Neelkanth on the western wall of the fortress has some spectacular art, and is a huge draw for pilgrims. As the sun was lowering in the west, we rushed past the day-tripping locals down to the temple. A flight of sheer steps led down to the courtyard which contained the cave. The steps went past a continuous gallery of rock carvings, with sculptures of various sizes and eras jostling for space. Most are from the Chandella era, including numerous marvellously ornate ekamukha shivalingas, large sophisticated panels depicting fierce Bhairavas and Chamundas, and innumerable depictions of Shaiva yogis, pilgrims, dancing yoginis and votive lingams. At the southern end of the courtyard rose magnificent mandapa pillars in the Chandella style, built by Paramardideva, enclosing a homa pit. This led to the intricately carved doorway to the cave shrine, with gorgeous images of musicians, dancers, and deities from the Gupta era. Inside was the main lingam, a large blue stone one, with eerie eyes painted on it.

As the priest started the evening prayers with the cacophonous ringing of bells, we went on past the mandapa to a recessed pool. Opposite it, carved into the rock face, rose a colossal statue of Bhairava, all of 24 feet tall. Baring his teeth, the deity stood in a dancing posture, his 18 arms bristling with weapons and severed heads. A garland of skulls hung around his neck as he bestrode the world, his phallus erect. To his right was a smaller, but equally terrifying carving of an emaciated Kali/Chamunda.As the sun slowly dissappeared into the haze on the western horizon and the bells fell silent, it was time to return to the evening fire at The Sarai for a drink. God knows, after the wonders of Bundelkhand, I needed one!

Courtesy: Outlook Traveller